Solid-state battery technology at the industrialization tipping point.

The rapid development of the global new energy vehicle and energy storage industries has placed unprecedented high-level demands on battery technology regarding energy density, safety, and cost. The energy density of traditional liquid lithium-ion batteries is approaching its theoretical limit (approximately 300-350 Wh/kg), and the risk of thermal runaway persists due to the presence of flammable and explosive organic electrolytes. In this context, solid-state battery technology, hailed as the "ultimate solution for next-generation power batteries," is undergoing a historic transition from laboratory research to scaled manufacturing.

According to the International Energy Agency's (IEA) assessment framework, the Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of all-solid-state batteries has currently reached levels 4-5 overall. This means that the proof-of-principle for their core materials has been completed in the laboratory, and fundamental scientific issues have been largely clarified. The current focus and core task have shifted from "how to achieve high performance in a single sample" to "how to translate the performance advantages of the laboratory into mass-producible, commercially viable product competitiveness with high consistency and low cost." This is a grand systems engineering project involving multiple disciplines such as materials science, electrochemistry, mechanical engineering, and automation control.

1. Material-level challenges and breakthroughs: the quest for the "perfect" solid core

The most fundamental difference between solid-state batteries and traditional liquid batteries lies in the complete replacement of the liquid electrolyte and separator with a solid-state electrolyte. This transformation brings potential safety and performance benefits, but finding a "perfect" solid-state electrolyte that combines high ionic conductivity, excellent stability, and good mechanical properties has become the primary challenge.

1.1 Evolution of solid electrolyte materials: a tripartite competitive landscape

Current research on solid electrolytes has formed a tripartite landscape dominated by oxide, sulfide, and polymer systems, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. The competition among these technical routes is far from over.

Sulfide Electrolytes: The Gifted Sprinter Requiring Strict Management

Sulfide electrolytes are undoubtedly the "top student" in ionic conductivity, with room temperature ionic conductivity (up to the order of 10⁻² S/cm) even comparable to liquid electrolytes, ensuring excellent fast-charging potential. However, this "athlete" is inherently sensitive—extremely poor chemical stability. Its reaction with moisture in the air produces highly toxic hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) gas, which imposes extremely stringent requirements on production environment humidity control (typically requiring ultra-dry environments with a dew point below -60°C), significantly increasing manufacturing costs. Furthermore, its interface with high-voltage cathode materials is unstable, prone to side reactions.

Recent breakthroughs show that lattice engineering through halogen element (especially chlorine) doping can effectively widen the electrochemical window of sulfide electrolytes and form a stable passivation layer on their particle surfaces, significantly improving their chemical stability. This modification suppresses H₂S generation while largely preserving their inherent high ionic conductivity, creating a key prerequisite for scaled production.

Oxide Electrolytes: The Steady Guardian Needing "Dredging"

Oxide electrolytes (e.g., LLZO: Lithium Lanthanum Zirconium Oxide) are known for their excellent chemical and electrochemical stability, reacting minimally with cathode and anode materials and being very stable in air, making them a paradigm of safety. Their shortcoming lies in their generally low bulk ionic conductivity at room temperature (typically in the range of 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻³ S/cm), and the rigid "solid-solid contact" with electrodes leads to poor interfacial contact and high interfacial impedance.

Recent research in interface engineering has brought hope. By introducing a functional transition layer (an "interface buffer layer") between the electrode and electrolyte, successfully acting as an "efficient translator." For example, using Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD), an ultra-precise coating technology, nanometer-thin buffer layers such as Li₃PO₄ or LiTaO₅ can be prepared. This thin layer can effectively block side reactions while significantly improving interfacial wettability; reports indicate it can reduce interfacial impedance from over 1000 Ω·cm² to below 100 Ω·cm². This technology addresses the key bottleneck in ion transport without significantly sacrificing energy density.

Polymer Electrolytes: The Flexible, Easily Processed but "Cold-Shy" Material

Polymer electrolytes, represented by PEO (Polyethylene Oxide), have advantages in good flexibility, ease of processing into films, and acceptable interfacial contact with electrodes. However, their ionic conductivity is highly temperature-dependent, often unsatisfactory at room temperature, requiring temperatures above 60-80°C for proper operation, which limits their application in room-temperature electronic devices. Current research primarily focuses on forming "polymer-based composite electrolytes" by combining them with other inorganic electrolytes to compensate for their poor room-temperature performance.

1.2 Compatibility innovation for electrode materials: co-evolution for mutual prosperity

The introduction of solid-state electrolytes necessitates corresponding "compatibility evolution" of electrode materials.

Cathode Materials: From "Islands" to "Interconnected Continents"

In liquid batteries, the liquid electrolyte can permeate every corner of the cathode material. In solid-state batteries, the solid electrolyte cannot flow like a liquid, leading to low utilization of active materials within the cathode particles, often below 80%.

To solve this problem, researchers have developed a coating-doping synergistic modification strategy. By constructing a mixed conductive network with both ionic and electronic conductivity on the surface of cathode material particles (like high-nickel NCM), it's akin to building "micro-highways" for each active material particle. This enables efficient transport of lithium ions and electrons to the interior of the particles, increasing active material utilization to over 95%, while effectively suppressing interfacial side reactions.

Anode Materials: The "Holy Grail" Battle from Graphite to Lithium Metal

Solid-state batteries make the direct use of lithium metal anodes possible. Lithium metal possesses an extremely high theoretical specific capacity (3860 mAh/g) and the lowest electrochemical potential, making it the "Holy Grail" for enhancing battery energy density. However, lithium metal undergoes infinite volume changes during charge/discharge cycles, and the problems of dendrite growth and an unstable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) are fatal challenges, leading to low Coulombic efficiency (typically below 90%) and short cycle life.

The current research focus is on interfacial stability control. By constructing a three-dimensional porous scaffold structure (like carbon fiber networks, porous copper current collectors) for the lithium metal, a stable space is provided for lithium deposition/dissolution, suppressing volume expansion. Simultaneously, artificial means are used to pre-form a robust, uniform artificial SEI layer on the lithium metal surface, guiding uniform lithium deposition. The synergistic effect of these technologies has already enabled the Coulombic efficiency of lithium metal anodes to exceed 99.5% in the laboratory, approaching the threshold of practicality.

2. Systematic solutions for interface engineering - tackling the world-class problem of "solid-solid contact"

If materials are the foundation, then the interface is the soul. The biggest technical bottleneck of solid-state batteries stems from the difficulty in maintaining close and stable physical contact between two solid surfaces over time.

2.1 Solid-solid interface contact mechanism: a static challenge in a dynamic world

During charge and discharge cycles, electrode materials (especially silicon, lithium metal) undergo significant volume expansion and contraction (up to 10%-300%). In liquid systems, the liquid can flow to fill gaps; but in solid-state systems, this volume change directly causes separation between the electrode and electrolyte, creating micron or even nano-scale gaps. The ion transport path is instantly interrupted, and the battery's internal resistance increases sharply until failure.

In engineering, two complementary approaches are currently used to mitigate this problem:

Introducing a Flexible Interface Layer: Adding a polymer or composite layer with certain elasticity and plasticity between the electrode and electrolyte acts like a "spring cushion" to buffer stress.

Applying External Pressure: Applying a constant mechanical pressure of 1-3 MPa to the entire cell, "tightly hugging" it from the outside to force the interfaces to maintain contact. However, this requires the battery pack design to include a pressure application mechanism, adding system complexity.

The more cutting-edge "self-healing" interface design is even more ingenious. This design uses special polymers or composite materials that, when micro-cracks form at the interface due to cycling, can themselves flow or undergo chemical bond recombination under the battery's operating temperature or electric field conditions, automatically repairing these cracks. It is reported that such technology can increase the cycle life of cells by 2-3 times, showing great potential.

2.2 Optimization of interfacial ion transport: from "climbing mountains" to "galloping on plains"

Even with good physical contact, ions encounter significant resistance when crossing the interface between two different solid materials due to lattice mismatch, high energy barriers, etc. To address this, scientists have developed various "interface dredging" solutions:

Constructing a Gradient Interface Layer: Avoiding an abrupt "property jump" from the electrolyte to the electrode material, instead forming a transition zone with continuously changing composition and lattice constant through compositional design, achieving a "smooth transition" and reducing the ion migration energy barrier.

Introducing Interfacial Liquid Medium: Strictly speaking, this constitutes a "hybrid solid-liquid" battery (or semi-solid battery). Introducing a small amount of specially formulated liquid or gel electrolyte at the interface can greatly improve contact and form efficient ion transport channels. This is an important transitional technology in the current industrialization process.

Developing Topological Structure Interface Layers: Designing interface layers with vertically aligned nanochannels or three-dimensional porous structures provides numerous "dedicated highways" for ion transport, directly increasing the density and efficiency of conduction pathways.

The comprehensive application of these technologies has successfully reduced the interfacial impedance of solid-state batteries from the initial range of 500-1000 Ω·cm² to below 50 Ω·cm². This order-of-magnitude reduction directly translates into significantly improved rate performance, making fast charging of solid-state batteries no longer a distant dream.

3. Engineering innovation in manufacturing processes - from "handicraft pottery" to "modern assembly line"

While high-performance coin cells can be produced in the laboratory regardless of cost using manual pressing and precision sintering, scaled manufacturing requires high-speed, stable, and controllable industrial processes.

3.1 Breakthroughs in Thin-Film Fabrication Technology: The Pursuit of Density and Ultra-Thinness

The fabrication of solid electrolyte membranes has evolved from the initially simple and crude "dry pressing" to continuous tape casting, which is more suitable for continuous production. This process is similar to "making pancakes," where a slurry made by mixing electrolyte materials with binders and solvents is spread by a doctor blade onto a carrier tape to form a wet film of uniform thickness, which is then dried to obtain an electrolyte film with specific flexibility.

The more advanced Co-firing technology is a core breakthrough. It allows precisely stacking prepared electrolyte green tapes and electrode green tapes, then, in a single sintering process with precisely controlled temperature profiles and atmosphere conditions (e.g., inert gas protection), simultaneously achieving densification of the electrolyte layer and firm bonding with the electrode layer. This process can control the final product porosity below 5%, ensuring unimpeded ion conduction paths and effectively avoiding excessive growth of the interfacial reaction layer.

3.2 All-Solid-State Battery integration process: the art of microns

Stacking or winding multiple layers of cathode, electrolyte, and anode into a cell is a process step with extremely high precision requirements in all-solid-state battery manufacturing. The challenges are mainly reflected in:

Stacking Accuracy: The alignment deviation between layers must be less than 2 μm. Any slight misalignment can lead to local short circuits or active area loss.

Encapsulation and Pressure Maintenance: The battery casing (hard case or pouch) must be able to provide stable and uniform appropriate pressure (e.g., 1-3 MPa) to the cell throughout its entire lifecycle to maintain interfacial contact.

Low-Resistance Connections: The connection resistance between tabs and current collectors must be extremely small to avoid unnecessary energy loss and heat generation.

To this end, the latest automated stacking equipment commonly integrates high-precision machine vision positioning systems, capable of real-time identification and correction of layer positions, successfully controlling stacking accuracy within ±1 μm. In the encapsulation stage, the application of isostatic pressing technology ensures that the pressure applied to the cell is uniformly distributed in all directions, avoiding local stress that is too high or too low, greatly improving the consistency of overall interfacial contact conditions.

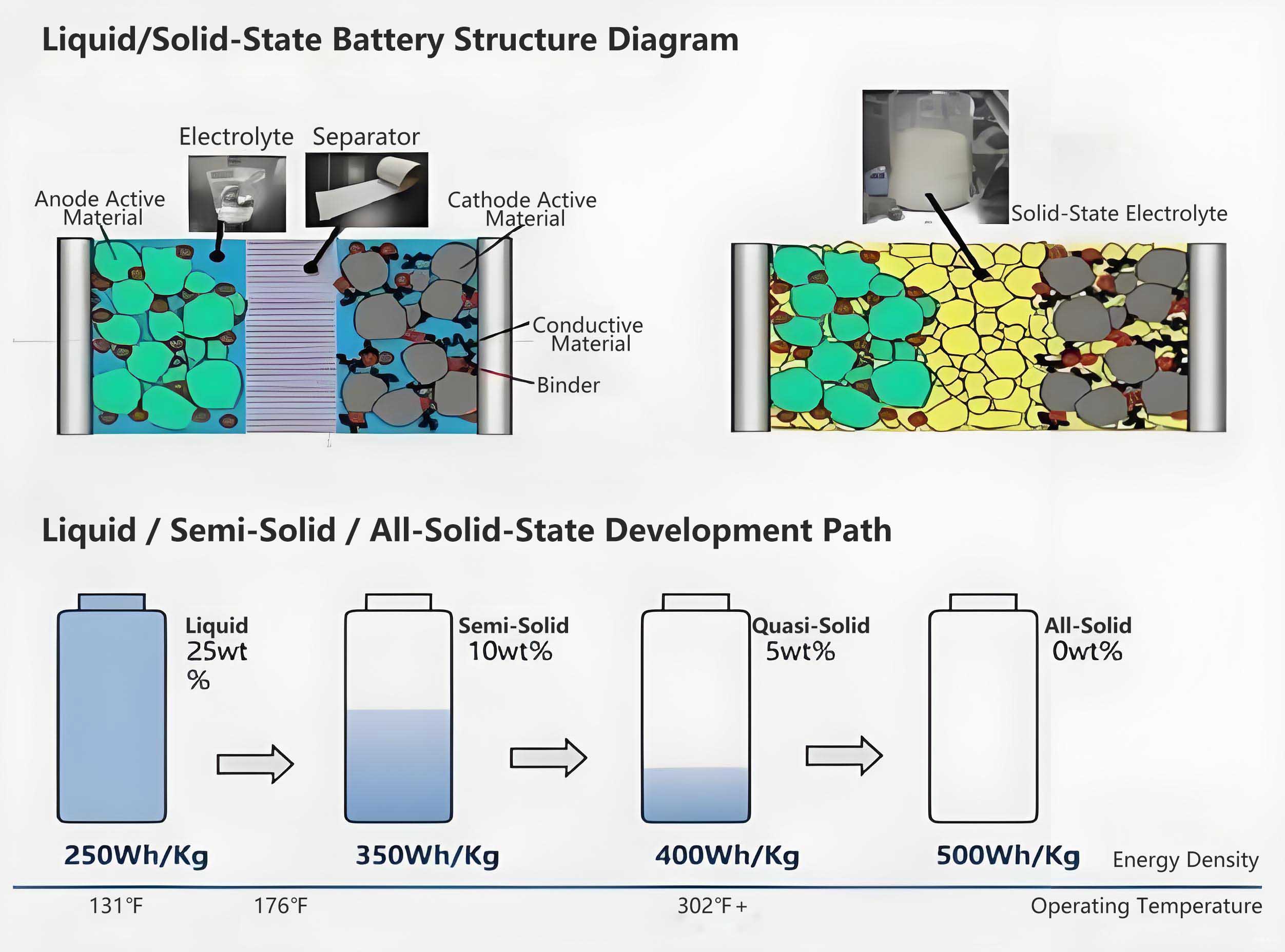

4. Systematic engineering for performance optimization - the roadmap to 500 Wh/kg

Through the breakthroughs in materials and processes mentioned above, the performance potential of solid-state batteries is being gradually unleashed.

4.1 Pathways for increasing energy density: a multi-pronged offensive

Increasing energy density is a systematic project, with main pathways including:

Increasing Cathode Material Capacity: Researching and applying new materials like lithium-rich manganese-based (LMR) and sulfur cathodes with capacities exceeding 220 mAh/g.

Reducing Electrolyte Layer Thickness: Using advanced film-forming technologies to thin the solid electrolyte layer from the initial hundreds of microns to below 30 μm, even approaching 10 μm, directly reducing the proportion of inactive materials.

Optimizing Electrode Structure: Adopting porosity gradient designs, for example, designing smaller pores near the electrolyte side to provide more reaction interface, and larger pores near the current collector side to facilitate electrolyte (in semi-solid) or ion penetration.

The synergistic effect of these measures promises to push the energy density of all-solid-state batteries beyond 500 Wh/kg, far exceeding the level of current top-tier liquid lithium-ion batteries (approx. 300-350 Wh/kg), laying the foundation for a thousand-kilometer range for electric vehicles.

4.2 Solutions for improving rate performance: making ions move faster

The rate performance of solid-state batteries was once questioned due to their "solid" nature. Now, it has been significantly improved through the following innovations:

Constructing 3D Ion Transport Networks: Designing interpenetrating ion channels inside the electrolyte or composite electrodes.

Optimizing Electrode/Electrolyte Interface Morphology: Increasing the effective contact area through surface roughening or constructing micro-interlocking structures.

Developing New Fast-Ion Conductor Materials: Such as discovering electrolytes with special crystal structures that provide low-energy-barrier ion migration channels.

Experimental data show that after adopting these technologies, the capacity retention rate of solid-state batteries at 3C rate (approx. 20-minute charge time) has increased from less than 50% in the early stages to over 85%, meeting the fast-charging requirements of most application scenarios.

5. Key technical indicators for industrialization progress - the trade-off between cost and scale

5.1 Cost control pathways: the transformation from "Noble" to "Commoner"

Preliminary analysis shows that material costs account for over 60% of solid-state battery costs, with the solid electrolyte itself, and the precious metals (e.g., Germanium, Tantalum) or high-purity raw materials used to adapt to it, being the main cost items. The path to cost reduction is clear but arduous:

Developing Low/No-Precious-Metal Electrolyte Systems: For example, replacing Germanium with elements like Tin or Silicon.

Improving Material Utilization: Increasing material utilization to over 95% through precise coating and reducing processing losses.

Optimizing Manufacturing Processes, Reducing Energy Consumption: For instance, lowering sintering temperatures, shortening process flows, achieving energy-saving manufacturing.

The industry generally expects that by 2026-2028, the manufacturing cost of solid-state batteries is expected to drop below $120/kWh, thereby initially possessing the ability to compete with high-energy-density liquid batteries.

5.2 Feasibility of scalable production: semi-solid first, all-solid follows

Transitioning from a laboratory "work of art" to a factory "industrial product" requires crossing a series of engineering gaps:

Determining and Controlling Process Windows: Establishing parameter ranges for each key process (like mixing, coating, sintering, stacking) and achieving stable control.

Equipment Selection and Production Line Layout: Selecting or customizing specialized equipment that meets technical requirements and designing efficient production line logistics.

Establishing a Quality Control System: Developing online/offline inspection methods to ensure product consistency and reliability.

Currently, semi-solid batteries, as the most pragmatic transitional solution, have begun small-scale production and installation in vehicles from brands like NIO and VOYAH. This provides the entire industry chain with valuable engineering experience, performance data, and market feedback, clearing many obstacles for the final industrialization of all-solid-state batteries.

6. Future technology development directions - beyond today's imagination

6.1 Exploration of new material systems: towards higher energy density and lower cost

The next generation of solid-state batteries may not be limited to current improvements but move towards entirely new material combinations:

Lithium Metal Anode paired with Sulfide Electrolyte: Pursuing the highest energy density.

High-Voltage Cathode (e.g., 5V class) matched with Oxide Electrolyte: Leveraging the advantage of high stability in oxides.

Polymer-Based Composite Electrolyte Systems: Seeking the best balance between processability, cost, and performance.

These new systems have great theoretical potential but face severe challenges in interfacial stability, cycle life, and manufacturing processes.

6.2 Intelligent battery system integration: empowering batteries to "Sense" and "Think"

The stable solid structure of solid-state batteries provides an ideal platform for integrating micro-sensors, evolving them into "intelligent batteries":

Embedded Sensors for Real-Time Monitoring of Interface Status: For example, using optical fiber sensors to monitor internal pressure and temperature distribution, or using impedance spectroscopy to analyze interface evolution in real-time.

Adaptive Thermal Management Systems: Controlling the battery operating temperature more precisely based on feedback from internal sensors.

State of Health (SOH) Estimation Based on Interfacial Impedance: Predicting remaining battery life earlier and more accurately by analyzing the trajectory of interfacial impedance changes.

These intelligent functions will greatly enhance the safety, reliability, and service life of battery systems.

Technological breakthroughs drive the industrialization process

Solid-state battery technology is undergoing a profound transformation from the laboratory towards industrialization. Through continuous innovation in material systems, meticulous work in interface engineering, engineering innovations in manufacturing processes, and system-level optimization design, its core performance indicators and manufacturing costs are approaching the threshold of commercialization at an unprecedented pace.

Although numerous challenges still lie ahead—such as the environmental tolerance of sulfide electrolytes, the cycle stability of lithium metal anodes, consistency and cost control in all-solid-state systems—the technical foundation for industrialization has been largely laid, and the development path is becoming increasingly clear. It is expected that within the next 3-5 years, we will first see the scaled application of all-solid-state batteries in high-end consumer electronics, special aerospace, and other fields. Subsequently, as the industry chain matures and costs decrease, it will gradually penetrate the high-end electric vehicle market and eventually expand into broader markets like large-scale energy storage.

The speed of this process will no longer depend solely on breakthroughs in single technologies, but more on the level of coordinated development of the entire industry chain—materials, interfaces, processes, equipment—as well as sustained capital investment and market patience. The dawn of the solid-state battery era has arrived, and a revolution in the power and energy storage fields is poised to begin.

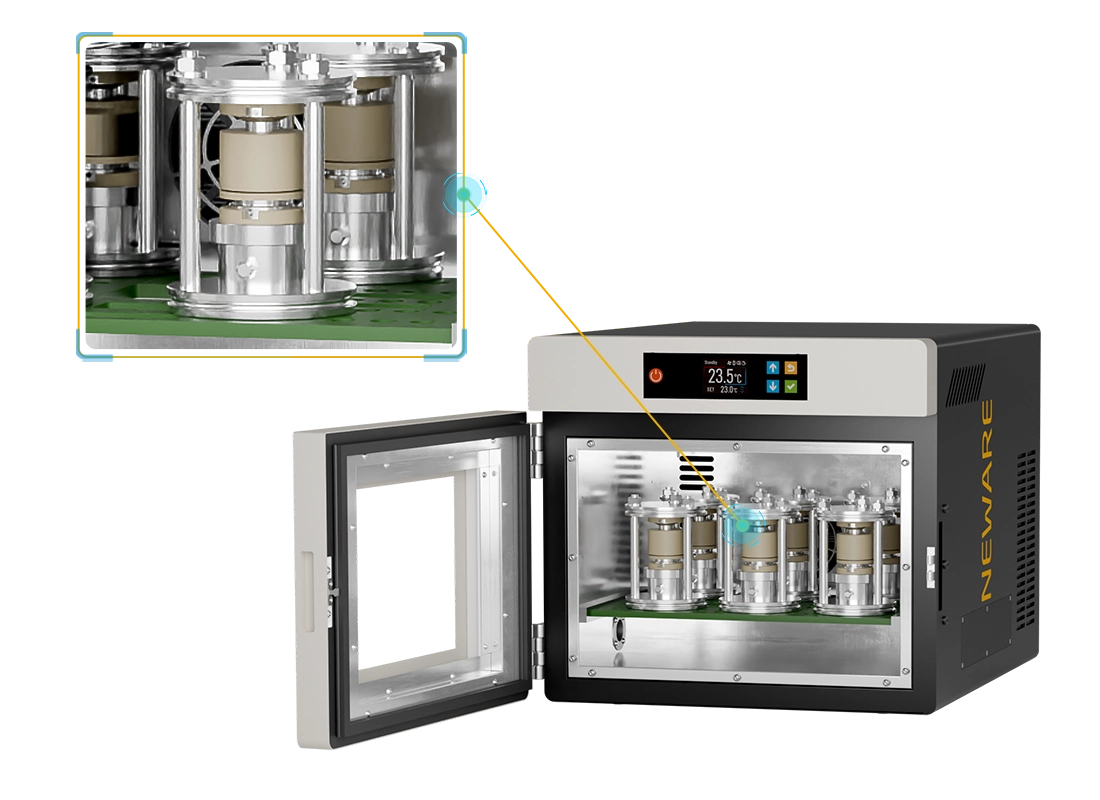

As a precision control expert in the field of solid-state battery research, NEWARE battery testing systems are equipped with high-precision current and voltage control functions, enabling precise regulation of the charging and discharging processes and optimizing battery performance. Additionally, we feature professional temperature monitoring and management systems, laying the foundation for the safe and efficient application of this innovative energy storage technology. For more details, please explore our solid-state battery solutions, offering you comprehensive one-stop services.

Supplement: Some of the above materials are from the Internet. We are very sorry if there is any infringement! You can contact us for deletion!