Battery tester: advanced capabilities and core performance requirements

As of 2025, various types of batteries are ubiquitous in our daily lives. The growing market demand for batteries presents significant challenges for their production, testing, and maintenance. Consequently, the performance of battery testers has continuously improved. High-performance battery testers are now capable of not only basic charge-discharge tests but also multiple electrochemical characterizations, such as CV (Cyclic Voltammetry), EIS (Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy), GITT (Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique), DCIR (Direct Current Internal Resistance), and other electrochemical tests. The foundation for ensuring the reliability of all this test data lies in the precision, accuracy, and stability of the battery testers.

Precision

Definition: Also known as repeatability, it refers to the closeness or degree of agreement between the results of multiple repeated measurements of the same measurand under identical conditions. It reflects the magnitude of the instrument's random error.

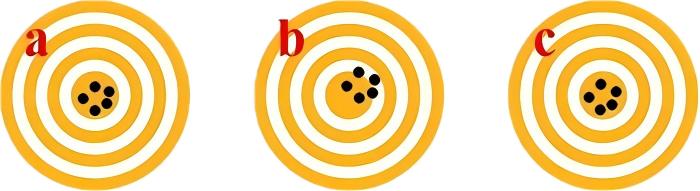

Role: Ensures Data Reliability: High precision means the test results have good reproducibility. Regardless of whether the measured value is absolutely correct, the results from each measurement are very similar, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Left: High Precision and High Accuracy; Right: High Precision and Low Accuracy

Consequently, it can be utilized to identify minute variations during the testing process. In battery research and development, it is essential to monitor subtle attenuation in a battery's internal resistance or capacity. Only a high-precision instrument can reliably distinguish these minor changes without them being obscured by its own measurement noise. In simple terms, precision addresses the question: "Are the measurement results consistent?"

Accuracy

Definition: Refers to the closeness of agreement between a measurement result and the true value of the quantity being measured. It reflects the magnitude of the instrument's systematic error.

Role: Ensures Data Authenticity: Accuracy determines whether the numerical value you read corresponds to the true physical value (Figure 2). For instance, if a tester displays a battery's internal resistance as 1.000 mΩ, its accuracy determines whether this value is a true and reliable 1.000 mΩ or is biased (e.g., the actual value is 1.050 mΩ). Accuracy is typically used for absolute evaluation. In applications such as battery sorting and quality inspection, determining whether a battery meets specifications must rely on accurate measurements of its internal resistance and voltage. Simply put, accuracy answers the question: "Is the measurement result close to the true value?"

Figure 2: Left: High Precision and High Accuracy; Right: Low Precision, High Accuracy

Stability

Definition: Refers to the ability of a measuring instrument to maintain its precision and accuracy over a period of time. It reflects the drift in the instrument's performance due to environmental factors such as time and temperature.

Role: Ensures Long-term Reliability: An instrument may have high precision and accuracy when it leaves the factory. However, if its stability is poor, its performance can degrade significantly after several months of use or with changes in ambient temperature. The level of stability directly relates to the required calibration frequency. Instruments with high stability can maintain their performance for extended periods without the need for frequent factory returns or recalibration, thereby reducing maintenance costs and the risk of operational downtime. Simply put, stability answers the question: "How long can the instrument's performance remain unchanged?"

The relationship between the three

Precision is the foundation for accuracy. An instrument with very poor precision produces highly scattered measurement results. Even if calibration adjusts the average value closer to the true value (improving accuracy), the result of any single measurement remains unreliable. High accuracy generally requires high precision as a prerequisite.

High precision does not equal high accuracy (shown as Figure 1). This is the most common point of confusion. As illustrated in the figures above, all bullets may hit the same spot (high precision) but could miss the bullseye (low accuracy). This typically indicates the presence of a repeatable systematic error in the instrument, which can be corrected through calibration.

Stability is the safeguard for precision and accuracy over time. Precision and accuracy are typically performance indicators of an instrument at a specific point in time. Stability determines whether these performance metrics can be consistently maintained throughout the instrument's entire lifecycle. An instrument with poor stability may possess "high precision and high accuracy" today, but that performance could vanish tomorrow.

The importance of calibration

If a high-precision, high-accuracy instrument is used without regular calibration, the following situation may occur initially:

The instrument's precision continuously decreases with increasing usage time (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Instrument accuracy shows a slight decrease, while precision shows a significant decrease

The instrument's accuracy continuously decreases with increasing usage time (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Instrument precision shows a slight decrease, while accuracy shows a significant decrease

After prolonged use, both precision and accuracy decline (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Both instrument accuracy and precision show a significant decrease

After prolonged use, the physical characteristics of the core reference sources within the equipment (such as voltage reference chips, precision resistors, and amplifiers) undergo gradual changes over time, due to temperature cycling and operational hours. This leads to systematic shifts in the measurement's "zero point" and "gain," resulting in decreased accuracy. This is the systematic error most in need of correction through calibration. Furthermore, environmental factors like temperature, humidity, dust, and electromagnetic interference, when accumulated over the long term, can cause changes in component parameters or introduce additional noise. This makes test values scattered or drift, manifesting as decreased precision. Additionally, repeated plugging and unplugging of device interfaces, thermal stress from switching high currents, and occasional overloads or accidental shorts can all contribute to the degradation of both the accuracy and precision of the equipment.

Calibration and correction

Calibration is not simply "zeroing" the instrument but a systematic process of qualification and correction.

Traceability: The device is sent to an accredited metrology institution. This institution uses "standards" that are at least one order of magnitude more precise than your device. The values of these standards are traceable, step by step, to national or international standards.

Comparison and measurement: The institution uses these standards to generate a series of known, absolutely accurate voltage, current, and resistance signals across the full measurement range of your device.

Recording deviation: A deviation table is created, recording the differences between your device's displayed values and the true values from the standards.

Correction (the critical step):

Software correction: The deviation table (correction coefficients) is written into the device's firmware. Thereafter, every measurement is automatically corrected using these coefficients, functionally restoring accuracy.

Hardware adjustment: Internal reference potentiometers are adjusted (less common in modern high-end devices).

Calibration primarily and directly restores and guarantees accuracy. By forcing the correction of the device's systematic errors against an external, higher standard, it brings measurement results back close to the "true value." It indirectly verifies and maintains stability. By comparing current calibration data with historical data, the drift rate of the device's performance can be assessed to determine if its stability remains excellent. Calibration typically cannot significantly improve precision. If the device's repeatability (precision) has deteriorated, it often indicates increased hardware noise or significant aging, which may require repair rather than calibration alone. The repeatability test data within the calibration report can be used to judge whether the precision meets specifications.

After calibration and correction, the device's accuracy can be restored to an excellent level. However, since the decrease in precision is partly caused by component aging, the actual measurement results will show a slight decrease in precision compared to the original factory performance. Nevertheless, because the actual usable lifespan of components generally exceeds the device's rated service life, and given the increasingly high quality of modern components, this has a very minimal impact on test data (Figure 6).

Figure 6 a: High Accuracy, High Precision; b: Before Calibration (Slight Decrease in Accuracy); c: After Calibration (High Accuracy, High Precision)

Conclusion

Precision, accuracy, and stability are all critical metrics for evaluating the reliability of data from battery testers. Even products with extremely high accuracy upon leaving the factory will rapidly lose their inherent high precision, high accuracy, and stability without proper maintenance and calibration, potentially degrading even further.

NEWARE has developed multiple calibration devices, which currently cover a range of product series. We offer regular on-site calibration services for our users, ensuring that their test data consistently maintains reliability and stability.